People have been producing questionable translations for as long as great literature has existed to be tarnished – and no literature, perhaps, has gotten worse treatment than Chinese.

English translations of Chinese tend to be what we might call “exoticised.” Nobody talks that way in English – and mimicking the grammar rules of the original text creates a mystique which, while sometimes attractive, is also deceptive.

If an author is writing in a way that flows naturally and coherently in their native tongue, that’s how it should flow in the translation. And if the author isn’t writing in riddles but offering a clear instruction or admonishment, then the translation shouldn’t be abstruse and artificially mystified.

To otherwise diverge in favor of a fortune cookie-like, literalistic translation is to shy away from the translator’s most sacred responsibility – to boldly state: I’m competent enough in this language and cultural context that I know what this person was talking about – regardless of the exact words used – it and was this…

That’s the paraphrastic argument – which I’ve discussed in much greater detail here.

The literalistic refrain is that nobody knows with absolute certainty what a particular author actually meant. We shouldn’t put words in people’s mouths, but strive for translations that are literal enough to be open to more or less the same range of interpretations as the original text.

Whichever way one leans – paraphrastic or literalistic – the goal is to strike an optimal balance according to the nature of the text being translated.

There’s one classical text in particular, though, where I don’t see this balance being struck.

Sunzi’s Military Methods

Sunzi (commonly translated as “Sun Tsu’s Art of War”) is an interesting case study, as it’s almost equal parts practical and philosophical – where the practical calls for clear paraphrasing, and the philosophical for literality open to wider interpretation.

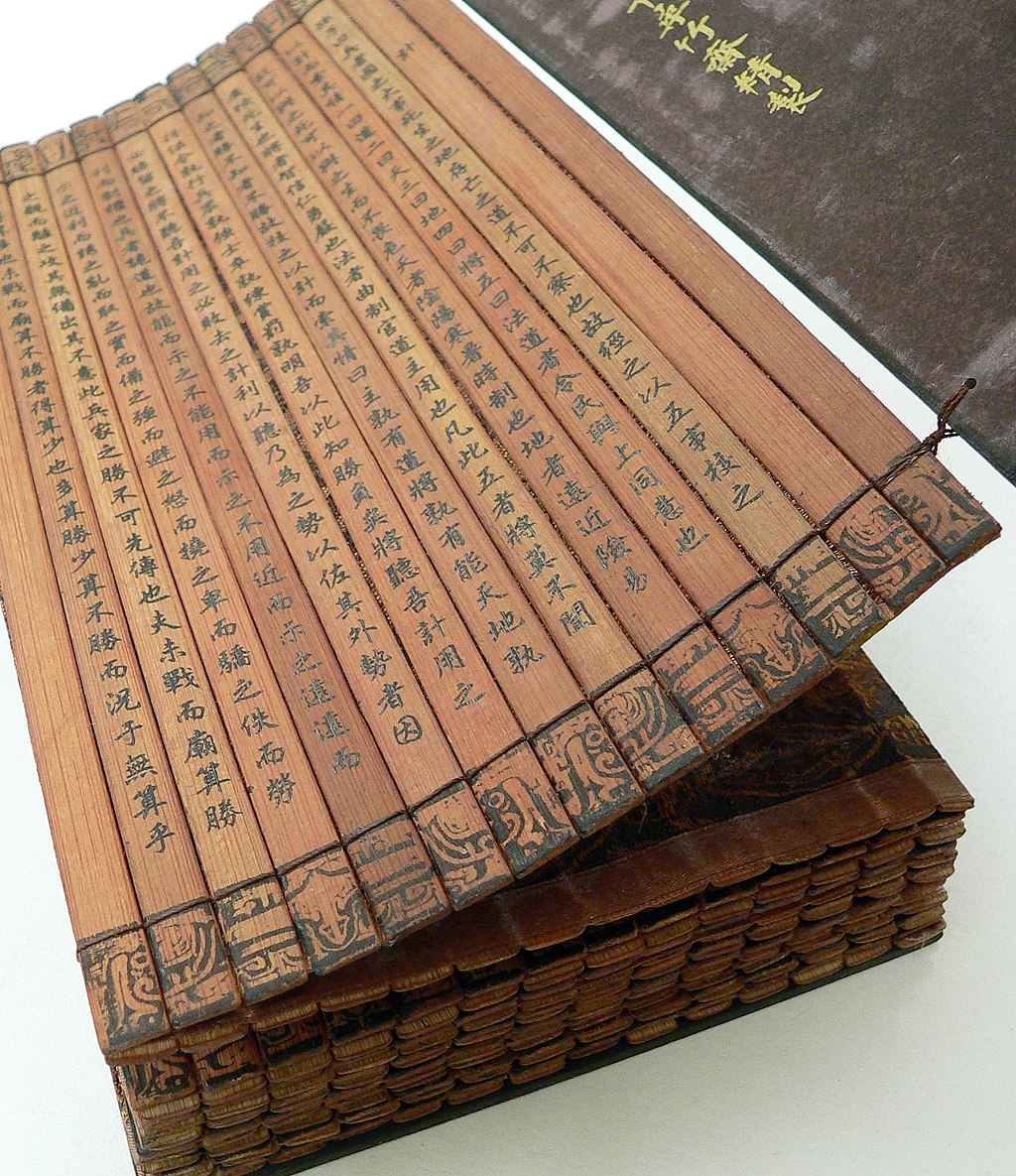

In the text that follows, I will be retranslating Sunzi from the beginning – as well as, of course, from a print of the original Old Chinese text.

To be clear, though, I’m not doing this because no decent (or even better) translation of Sunzi exists.

I’m doing it because libraries all over the world are filled with renderings of Sunzi by respected translators that nevertheless make me cringe – not because they’re inaccurate, but because they simply aren’t what I see when I read Sunzi.

They don’t feel like what Sunzi the man was trying to actually say.

Many instead are Frankenstein’s monsters of disparate word-for-word translations that are technically correct, but don’t fit together. They’re uncanny, forced, and patronizing, like your parents trying to sound hip by using the latest slang when trying to convince you to do something.

Normally when I translate a Classical Chinese (文言文) work, I try to capture the best of both worlds – literal and paraphrastic – in one text.

This time, I’m going to do things differently, giving myself permission to go extra-paraphrastic by supplementing every line I translate with a more (but not completely) literalistic alternative.

Chapter 1: Initial Calculations (始計)

孫子曰兵者國之大事死生之地存亡之道不可不察也

Literal: Sunzi said: “War is a matter of great importance to the state. It is the ground of life and death – the path to survival or destruction – and it cannot go unscrutinized.”

Paraphrastic: For the state, war is a matter of the utmost importance. It's a matter of life or death – survival or extinction. And how one wages war therefore shouldn’t be left to whim, but should be carefully scrutinized.

So far, not much of a difference – though I did add “shouldn’t be left to a whim” to smooth things out, as it seems to be implied.

I actually prefer parts of the more literal translation in this case for their aesthetic. Still, I think the paraphrastic version is going to prove more useful as things get more complex (like in the next paragraph).

故經之以五事校之以計而索其情一曰道二曰天三曰地四曰將五曰法

Literal: Thus, there are 5 things [we] must calculate to gather the reality [of the situation]: the first is called “command;” the second is called “the celestial;” the third is called “the terrestrial;” the fourth is called “general[manship];” and the fifth is called “law.”

Paraphrastic: To do this, we have to make a few (the number 7 is specified in some prints) calculations based on 5 considerations: 1) The commanding quality (“command”) of the leadership; 2) various weather-related environmental conditions (“the celestial”); 3) the advantages and disadvantages of different terrain (“the terrestrial”); 4) the competence of the generals in command (“generalmanship”); 5) and how (and the extent to which) order is maintained (“order”).

Now the difference is becoming more apparent. Sure, I’m reading between the lines – but I’m doing so having already read and understood the full text, and referenced multiple commentaries to make sure the implications I’m making explicit are accurate (or at least accepted by the academic community).

Anyway, the key point is that if Sunzi were alive today and spoke modern English, this is how I think he would write – clear, coherent, and no-nonsense.

道者令民與上同意可與之死可與之生而不畏危也

Literal: Command means aligning the people’s will with the leadership, [so that] they can live and die by him without fear of the danger [involved].

Paraphrastic: “Command” is a leader’s ability to inspire people to follow him in life – and to their deaths – without fear of the dangers they face.

Note that some translators go even further than I have in my literalistic interpretation, directly translating (transliterating) “command” as “Tao” (道) – as in the Tao of the “Tao Te Ching.”

Based on Sunzi’s own definition of “Tao” as a kind of charismatic quality of leadership, however, “command” seems like a pretty excellent stand in.

天者陰陽寒暑時制也

Literal: “The celestial” means sun (yang) and shade (yin); hot and cold; [and] the seasons.

Paraphrastic: “The celestial” refers to environmental conditions such as the season, temperature, weather, and time of day.

The two main commentaries I’m referencing for my translation of Sunzi are 孫子讀本” (“The Sunzi Reader’s Booklet”) and “華杉講透孫子兵法” (“Hua Shan Breaks Down Sunzi’s Art of War”) (these English titles are my own tentative translations).

Incidentally, they disagree about what yin and yang (陰陽) refers to here – and this kind of controversy might be an argument in favor of not interpreting the term at all, but rather just leaving it as it is. That way readers can develop their own interpretations based on their understanding of all the different things “yin and yang” might mean.

Is the reader with a scholarly knowledge of all the things yin and yang can mean who this kind of translation is really for, though? Maybe it will fall into the hands of a Chinese researcher who doesn’t speak the language, for example – but in most cases it will be for the layman.

Anyway, the latter commentary proposes yin and yang is referring to qi while the former proposes it’s referring to whether it’s daytime or nighttime, cloudy or sunny (i.e. “sunlit” or “shady”).

I’m going with the latter not because the former isn’t plausible, but because it isn’t helpful. Sunlight and time of day come up later in “Sunzi” (for example, what times of day are best for setting the enemy on fire) – qi does not.

地者高下遠近險易廣狹死生也

Literal: “The terrestrial” means [all to do with] high and low [ground]; short and far [distances]; precarious and surmountable [terrain]; wide and narrow [passes]; and death [traps versus] survivable [positions].

Paraphrastic: “The terrestrial” refers to considerations about elevation (such as who has the high ground and who has the low ground); relative distance (especially in regards to routes between different points); difficult terrain (mountains, forests, etc. vs. flat, open terrain; berth (such as how narrow or wide a valley or pass is); and survivability (whether a given area is a feasible position [生地] or a death trap [死地]).

將者智信仁勇嚴也

Literal: “General[manship]” means intelligence, trust, benevolence, courage, and stringentness.

Paraphrastic: “Generalmanship” is determined by a general’s intelligence, trustworthiness, compassion, bravery, and the discipline he enforces.

法者曲制官道主用也

Literal: “Law” means unit structure, officer hierarchy, and spending.

Paraphrastic: And “order” refers to the system by which troops are organized into units; the chain of command; and finances and logistics.

I’ll just note here that I came across a research paper that suggests “zhuyong” (主用) while commonly interpreted as finances and logistics, may alternatively mean “a leader’s (or emperor’s) spending” based on the literal meaning of the characters.

Again, as in the case of “yin-yang,” while both are plausible, it’s obvious which definition is more useful – and this will be even more obvious when we begin the next chapter, which dives straight into logistics.

For now though, we’ll stop here, and I’ll continue this chapter on "initial calculations” with more commentary (and a new theme) in the next article.

Uninterrupted Translation:

For the state, war is a matter of the utmost importance. It's a matter of life or death – survival or extinction. And how one wages war, therefore, shouldn’t be left to whim, but should be carefully scrutinized.

To do this, we have to make a few calculations based on 5 considerations: 1) The commanding quality (“command”) of the leadership; 2) various weather-related environmental conditions (“the celestial”); 3) the advantages and disadvantages of different terrain (“the terrestrial”); 4) the competence of the generals in command (“generalmanship”); 5) and how (and the extent to which) order is maintained (“order”).

“Command” is a leader’s ability to inspire people to follow him in life – and to their deaths – without fear of the dangers they face.

“The celestial” refers to environmental conditions such as the season, temperature, weather, and time of day.

“The terrestrial” refers to considerations about elevation (such as who has the high ground and who has the low ground); relative distance (especially in regards to routes between different points); difficult terrain (mountains, forests, etc. vs. flat, open terrain; berth (such as how narrow or wide a valley or pass is); and survivability (whether a given area is a feasible position [生地] or a death trap [死地]).

“Generalmanship” is determined by a general’s intelligence, trustworthiness, compassion, bravery, and the discipline he enforces.

And “order” refers to the system by which troops are organized into units; the chain of command; and finances and logistics.